My Body Is Being Battered and Broken by an Unlikely Tormentor: Books. - Slate

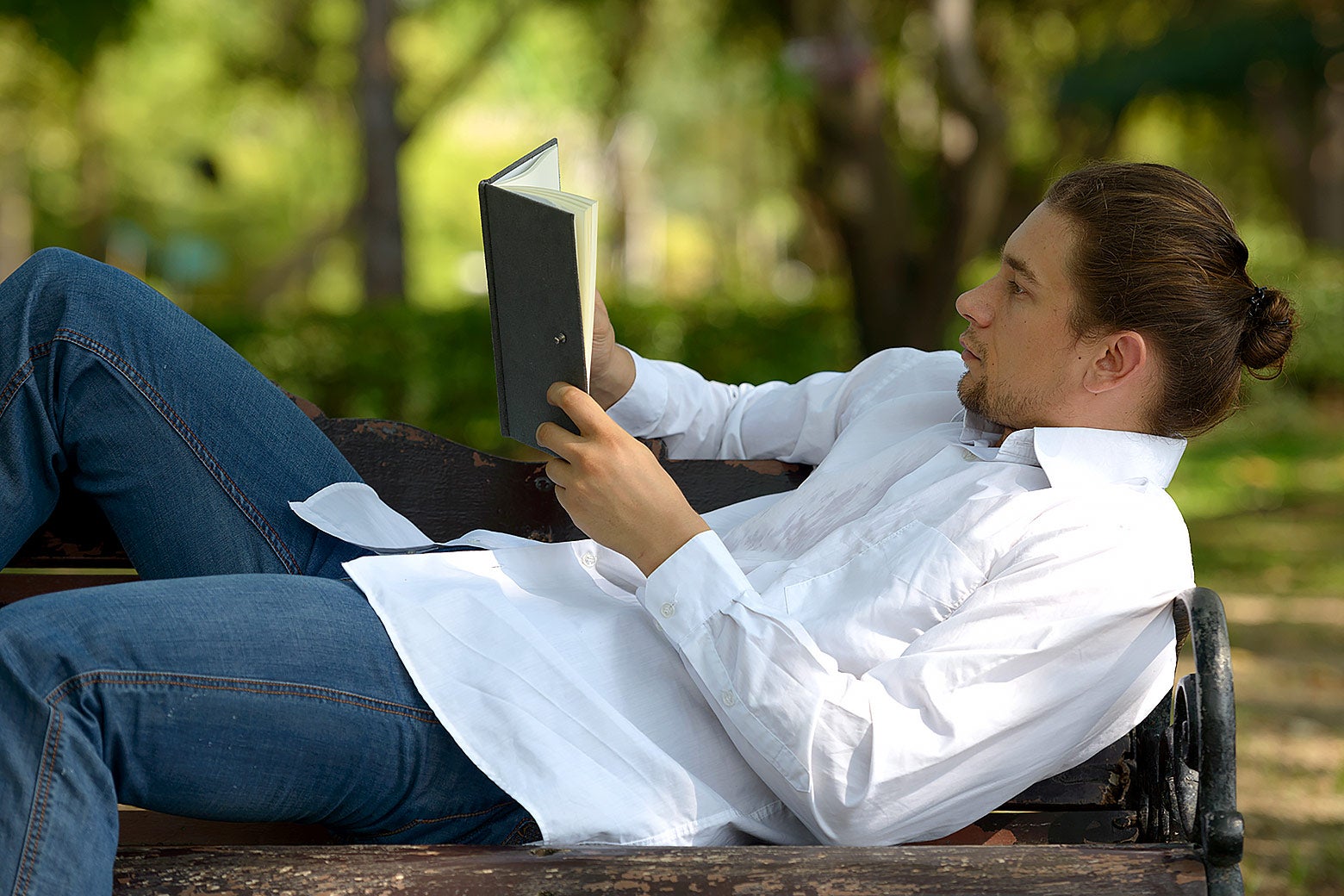

Enter your email to receive alerts for this author. Sign in or create an account to better manage your email preferences. Are you sure you want to unsubscribe from email alerts for Luke Winkie? Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily. For the 10th year in a row, my New Year’s resolution is to read more books. Ideally, as I tend to tell myself during these protean early weeks of January, 2026 will be remembered for languorous evenings on the couch, tearing through the inventory of novels that crowd the modest capacity of my living-room shelves, perhaps with a tumbler of scotch resting on a coaster. I revel in the fantasy—I dream about finally cracking open A Confederacy of Dunces, or knocking out the last two entries of the Broken Earth trilogy, or making time for that Patti Smith memoir that I bought more than a decade ago. If I’m really feeling myself, I contemplate aiming even higher. Tolstoy? Pynchon? I mean, there’s also that copy of The Pale King that has been steadily yellowing on my coffee table for quite some time now. And yet, I already know how this saga is going to end. The year will draw to a close with a piddling number of new entries to my Goodreads, hopelessly incongruous with the size of my bibliophilic ambitions. Ask me why I never seem to read as much as I like, and I could gesture toward the well-worn afflictions of modernity—ballooning screen time, addictive algorithms, frayed attention spans. But one of my fundamental issues with literature is far more prosaic. In fact, I think it’s much more common than anyone would like to admit. Why is it that no matter what I do, I can never get comfortable while reading a book? Don’t act like you don’t know what I’m talking about. This is a species-wide affliction. The first published novel in history is widely considered to be The Tale of Genji, a courtly drama written in the late 11th century by the Japanese noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu. A millennium since her wondrously mind-expanding invention, humanity has somehow yet to conceive an ergonomically sound way to consume the written word. I, like you, have lain flat on my back holding a novel aloft until my arms grow strained, fidgety, and unable to maintain equilibrium. I have also sat in an armchair, splaying the book open in my lap, until the severe angle stiffens my neck and reinforces the horrible truth that furniture was never meant to support the literary necessity to gaze downward. There is, of course, always the option to flip over to your stomach, allowing your elbows to dig into the mattress, carpet, or couch cushions. That works for a spell, until it becomes clear that your body is situated in a tedious, low-impact plank, while, in the pages below, Raskolnikov brandishes his axe and kills everyone in sight. I cycle through all of these postures, over and over again, hoping to finally crack the code—unlocking the sublime Zen of the novel, the fabled joys of reading. When I put out the call to my friends and colleagues to see if they related to my plight, I quickly learned that all of us are languishing on this futile journey. Slate associate editor Bryan Lowder recalled that while leafing through a supremely unwieldy hardcover tome containing the collected Earth Sea novels, he was forced to stack three pillows against his headboard and another on his abdomen in order to remain sound of body while tracing the adventures of Sparrowhawk. My friend Laura Grasso—a costume designer, and a woman who recently finished The Brothers Karamazov—has developed a complicated anthropometrical schematic in which she props her entire body on the padded slope of a couch’s armrest, with the book balanced delicately in her eyeline. (“I try to go full diagonal,” she said. “That’s by far the most optimal approach.”) Others have developed a Stockholm syndrome–esque relationship with the agony of reading, interpreting the pain as a sign of virtue. Slate senior editor Tony Ho Tran said that he is of the opinion that he “needs to be a little uncomfortable” to concentrate on his literature. “Give me a weird wooden dining chair,” he proclaimed. “Give me a plastic seat on the train while I commute.” Surely it doesn’t have to be this way, right? Shouldn’t we, as a species, have evolved to possess some sort of natural lumbar support—or some bracing callouses—to assist in the time-honored tradition of reading words printed on paper? Can it be that Moses, descending from Mount Sinai with stone tablets consecrated by God himself, was left with a sore neck while deciphering the Ten Commandments? Well, according to Ryan Steiner, a physical therapist at the Cleveland Clinic, the answer is yes. Reading, as it turns out, forces the body into a totally unnatural form. There’s nothing any of us can do. “Honestly, we’re not meant to stay in one position, even if it is a comfortable position, for an extended period of time,” said Steiner. “You should be changing positions often when you’re reading. I recommend getting up and moving around every so often.” Steiner happily broke down the physics for me. Threaded throughout our nervous system are microscopic electrical sensors called “mechanoreceptors.” These nerves alert our body to the way we’re stretching, compressing, or otherwise adding tension to our soft tissue. This is true if you’re doing deadlifts, and also true if you are holding a book in front of your face. “After a while, those receptors send a message to your brain like, ‘Hey, there’s something going on here, this doesn’t feel natural, you need to take action,’ ” said Steiner. This is when we adjust our dimensions to find a more comfortable position, repeating the circuit over and over again for as long as we have a book in our hands. Maybe you find it baffling that a novel could put the same pressure on our bodies as, say, a bag of concrete, but Steiner is quick to remind me that with enough time, just about anything can become unwieldy. “A little bit of force can still make a big difference. If you’re holding something relatively lightweight—like a 3-pound weight—down by your side, you could do that for hours. But if you’re holding it in front of your face? You might not be able to make it a minute.” For what it’s worth, the forces of technology are rising to meet the reading problem. We have all heard of bookstands, which can be installed in bed or in the bath, allowing one’s hands to be occupied by a chilly pinot noir while surveying a gooey romance novel. But those who prefer to read on tablets have taken matters much further. I reached out to Chelsea Stone, who works for CNN, and who recently reviewed a truly revolutionary contraption that fastened her e-reader to a modular silicone mount. She winched the neck of the crane over her mattress, letting the tablet hover gracefully in front of her eyes while she was lying in bed. To turn the pages, Stone used a Bluetooth remote. Her hands never needed to exit the covers. It was an airtight cocoon of literary bliss, reminiscent of those mobile lounge chairs employed by the sedentary refugees in Wall-E. Stone had rendered the human limit obsolete—banishing those damn mechanoreceptors—once and for all. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve dozed off with a book in my hands only to be woken by it smacking me in the forehead,” said Stone. “The stand gives me freedom to read in any position I want at the moment.” And yet, Stone, an avid bibliophile, tells me that she still likes to read books the old-fashioned way. I can understand why. A mount to hold your Kindle might be physically prudent, but it seems spiritually diminished to me. Ultimately, I like to read for the many accessories of literature; the way the ritual can brighten an ordinary day. Consider the accidental discovery of an ideal nook—a coffee shop, a park, a beach—ready-made for whatever novel you’re carrying around in your backpack. Time stops, and your imagination fissures open. My hip flexors scream for mercy as I lie on my side, quieting my mind. We’ve been reading books for a thousand years. Clearly, it must be worth the pain.